About the difficulties that you may encounter if you are engaged in the localization of war games.

Hello, my name is Stepan, and I’ve been working in video game localization studio Levsha since 2012. It’s a typical autumn day in Moscow today: pouring rain, with no promise of any warmth. To avoid falling into autumn completely, I suppose I’ll tell you about one of the most merciless wrinkles in game design. If my experience might help someone with their video game translation, then it’s worth trying to share that experience.

Seven years working in localization have given me an absolute treasure trove of information that has nothing at all to do with my chosen occupation. Agricultural industry, fishing, hunting, war. If you want quality results from your text, you’re going to have to learn a bit about things you hadn’t planned on ever knowing when you were on your way to the office.

![edf588604a179f736bc3f4b2b55c0292[1].jpg](https://static.tildacdn.com/tild3633-3434-4335-b265-656432363861/ss_27af5d7b29e17d5c1.jpg)

The most unusual and interesting projects from my early years getting to know localization were all to do with military themes. It was war without mercy, trial by fire. I was a newbie, and I’ll never forget my first project. Now it seems simple, but back then I couldn’t understand how it could even be done.

Any military-themed project will naturally be difficult to localize: the spheres of military operations, translation, and video games don’t often overlap. Of all project I’ve ever worked on or played myself, only 5% were without errors. It’s possible I just didn’t spot them. Or maybe, it was the case that those projects were worked on by people that knew their work.

Something Is Sure to Go Wrong

Even when the translator takes care to prepare, combat helmet at the ready, problems are sure to come up around differences in military jargon in different countries. Thanks, slang. Slang consists of familiar words in an unfamiliar context. Terminology and names often differ between countries. Add cultural differences, a lack of reference material, and complete radio silence from the client, and you get a lethal projectile guarantee to hit its mark.

Destroyer — разрушитель — эсминец

There are many words in the Russian language that can describe maritime power. But Эсминец is the most lovely of them all. This class of military was created to counteract just about any opponent: submarines, aircraft, other ships… Translating ‘destroyer’ as ‘разрушитель’ is a serious mistake of literalism, and must be avoided. Unfortunately, in-game text strings don’t always have an attached ID that might help understand what a segment is referring to. Is it a class of ship, a nickname?..

M1 Abrams — М-1 Авраам — М-1 «Абрамс»

The M1 Abrams is the primary battle tank of the United States Army. These combat vehicles gained a cult following in North America in the 20th century, and has been in mass-production since 1981. A child of the cold war, created to counteract Soviet tank design. There are few tanks that can claim such frequent mention in media culture, be it cinema, video games, comics, or animation. It’s hard to imagine that anyone might never have heard of it. But there’s nothing impossible in the field of localization: if the translator is working for the second day straight and the deadlines are burning, disaster is inevitable. Thankfully, any unwelcome ‘Ааврам М-1’ is sure to be escorted out by the editor. It’s worth remembering that too much haste can birth such localization monsters as can tear a game apart from the inside.

![WorldOfWarships5[1].jpg](https://static.tildacdn.com/tild6430-3830-4566-b464-346636303238/Abrams_Battle_Tank_g.jpg)

HMS Queen Elizabeth — Королева Елизавета — Куин Элизабет

The love of a captain for the ship knows no bounds. In the same way, the love a brit’ for the Queen also knows no bounds, but the love of a localizer to grammar standards is even stronger. The ‘Куин Элизабет’ is an air carrier in the service of Great Britain’s Royal Navy. Referring to the ship as ‘Королевой Елизавета’ would be a terrible mistake. A ship is named only once, and that name must not be changed, whether in life or a game. Even if the translator has personally set foot aboard a ship, they might not know that proper nouns and titles for vehicles are written through transliteration in Russian. This is a common mistake, not only around military themes, but in simulators involving watercraft.

![WorldOfWarships5[1].jpg](https://static.tildacdn.com/tild3862-6665-4631-b061-396464396533/ce98dbac-8317-11e7-a.jpg)

Situation is FUBAR — Ситуация ФУБАР — Нам пи***ц

FUBAR situation — fucked up beyond all recognition

FUBAR is synonymous with an unwinnable situation. This American military lingo comes to us from the Second World War, and is still in use today, having even been included in the Oxford Dictionary. If you’re in an unwinnable situation and located in North America, but you don’t want to repeat yourself, use the slang ‘Clusterfuck’ and you’ll be immediately understood. Difficulties in Europe? The NATO phonetic alphabet is here to help with the designation ‘Charlie Foxtrot’ for special circumstances. It’s inadvisable to use transcription here. FUBAR comes from military jargon, but a Russian player might not know these kinds of military terms, so any more common phrase that well characterizes a panicked disaster should make for an excellent replacement.

![WorldOfWarships5[1].jpg](https://static.tildacdn.com/tild3761-3833-4638-b530-376333373135/1457281348143544980_.jpg)

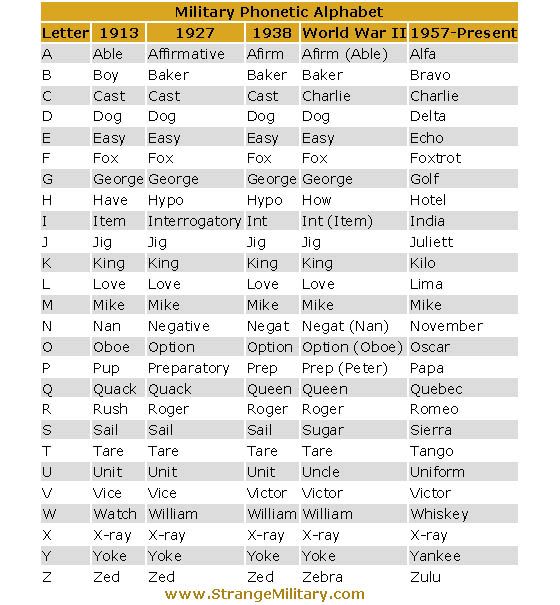

ML150 in air — Рейс Эм Эль 150 в воздухе — Майк Лима 150 в воздухе

If you’re working on a military game, you’re really going to need the NATO phonetic alphabet. It’s hard to come up with a greater romance than the one between the American military and the use of code words using the ICAO phonetic alphabet. Without knowing these references, localization might turn an America radio dispatcher into their Russian counterpart, who speaks using the impermissible ‘Эм Ель’ instead of the beloved ‘Майк Лима’, or even uses the Russian version of the phonetic alphabet instead, turning the flight into a ‘Михаил Леонид 150’.

In addition to its own special alphabet, all Russian military materiel has its own US and NATO designations, so don’t be confused if an ‘Су-27’ becomes a ‘Flanker’, while the ‘Тополь-М’ ends up a ‘Sickle’. It’s absolutely essential to check all names with the help of search engines and use reference materials like this one, which deciphers various naming conventions.

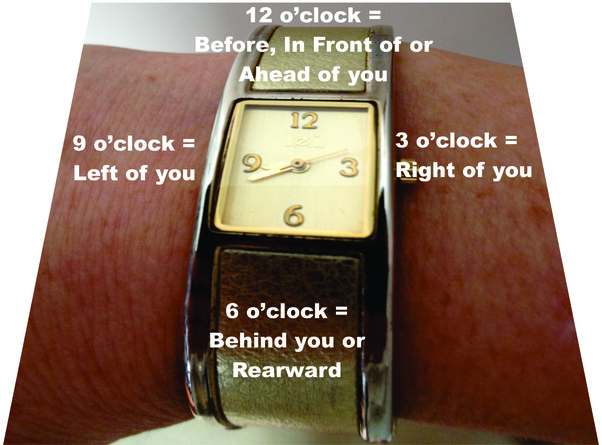

Watch your six

The most beloved idiom in a localizer’s life, coming to us from military slang. One of the most difficult lines for unprepared translators. To keep communications during battle short and provide precise position designators within a combat unit, militaries use the numbers on a clock face as a coordinate system.

Problems with these kinds of phrases happen a lot more often than anyone would like. The translator might have an excellent grasp of the text, but not notice a clearly odd phrase that must not be translated word-for-word..

- Feet are dry — «Лечу над сушей».

- Fire in the hole — «Граната! В укрытие!»

- Roger that — «Вас понял!»

Good examples of commonly used phrases like these can be found here. This kind of slang can become a serious issue during translation. If a phrase seems out of place in the text, it’s most likely that you’ve found some military slang.

Easy company — Легкая компания — 5-я рота — Изи компани

It’s important to know that the USA and NATO use their own naming system for military companies, based on the alphabet (ABCDE). Meanwhile, the Russian Federation uses a numeric system (12345). During localization, it’s important to understand that any division might have an E Company, which can be translated as ‘5-я рота’, but there has only ever been one Easy Company, represented as ‘Изи компани’ in text and VO, in all of history. The company, raised in 1942, quickly became the template for bravery and courage during the Second World War. It achieved immortality in popular culture thanks to the book “Band of Brothers” and the miniseries of the same name.

Everything seems clear enough. Different systems for division names, the phonetic alphabet, and a historic event. But go ahead and open up the NATO phonetic alphabet and check, what’s E? Echo. So where’d we get Easy? It would all be so simple, if only the US military’s phonetic alphabet hadn’t been redesigned several times. Created in 1913, up until 1957 the letter E was represented as Easy. So now, we have a little more clarity.

In conclusion, I’d like to recall an occasion that has nothing to do with localization. It’s a good example of how difficult it can be to convey information on military themes, where familiar words might change their meanings.

In the series The Pacific, an officer enters a trainee classroom. The sergeant commands: “Attention on the deck!” In Russian, this phrase was rendered as “Внимание на доску!”, which is wrong. The translator didn’t understand that the scene is showing a marine training course, where they use naval and maritime language and orders, which is why the sergeant was calling for attention on the deck.

It was interesting to recall the challenges I’ve left behind. I’m sure that, should I encounter a horse-breeding simulator, instead of military jargon, there’d be just as much from the disciplines of animal husbandry. That’s the thing with localization: you just can’t approach two projects the same way. There’s always going to something that stumps you. But figuring it out will always leave you feeling good, like nothing else can.