One of the biggest and long-term projects in our studio's history.

Shroud of the Avatar by Richard_Garriott, the creator of Ultima Online, was one of the biggest long-term projects in our localization studio’s history. If you started gaming on the PC in the early 90s, we’re sure Richard Garriott’s name rings a bell. Lord British is a pioneer in the world of video games who contributed to the establishment of both the MMORPG genre and the video games industry in general. He creates virtual worlds based on his real-life experiences: a dive to the site of the Titanic’s wreckage, the exploration of the Amazon rainforest, a flight to the International Space Station, and other adventures he describes in his book, Explore/Create, in great detail.

Unfortunately, Richard Garriott’s new project fell short of the success of the first games in the Ultima series, but the issues that surrounded SotA didn’t influence the localization process. As is often the case, the difficulty of localization was unrelated to the game’s success.

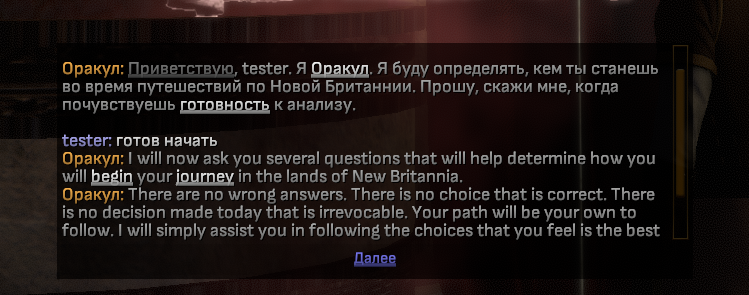

In Shroud of the Avatar, the player is inextricably linked with the plot. Those who have played Ultima Online will find it nostalgic: you can bind commands such as /Guards! or /Merchant to hotkeys. There’s one difference, though: you couldn’t send a command in Russian in 1997, whereas SotA does offer this opportunity. As you might have guessed from the comparisons with UO and mentions of Garriott, Shroud of the Avatar was designed as a hardcore MMORPG with a vast creative atmosphere and countless options for exploring New Britannia without any hints or clear directives. The player messages NPCs in the game chat for quests and information. The NPC recognizes keywords and provides the player with information on the location, the latest news, and quests. To complete a quest, you need to read carefully and ask around. There are no marks or directions for completing part-time jobs. Due to the game mechanics in Shroud of the Avatar, text is the primary means of exploring the in-game world.

However, it’s all much trickier from there. There are many keywords, and they can be encountered in different parts of the game. We needed to find all the triggers and localize them accordingly.

Here’s an example. A character named Peter Horse Ear has a set of phrases with triggers: words that activate an NPC’s speech ability, and which are highlighted in the text. You need to send one of these words in the chat to activate Peter and make him speak on the corresponding topic.

The main issue was to make sure the translation didn’t botch the logic of the English text, meaning that the number of keywords in Peter Horse Ear’s speech in the original and the Russian version needed to be the same. It could affect the difficulty of a play-through in the open-world game. We needed to remove the extra keywords from Peter’s speech if there were too many, or add them in the keyword list or Peter’s speech if there weren’t enough of them.

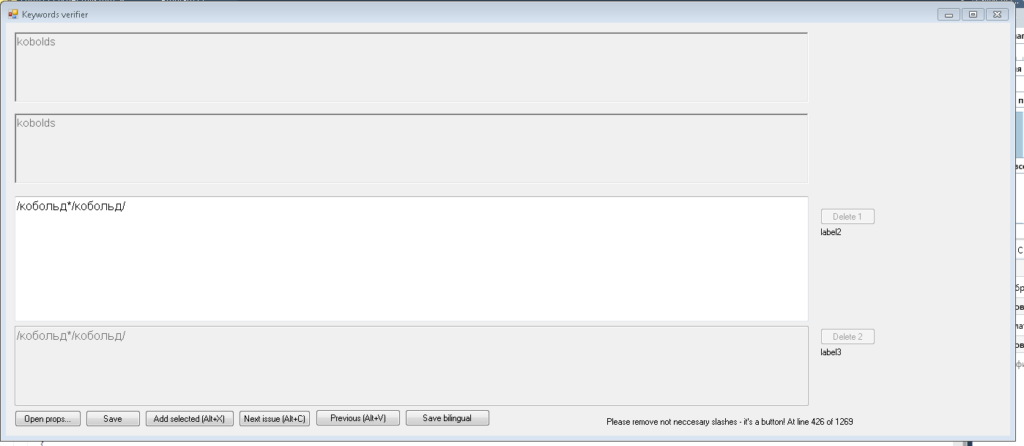

To retain the logic of the English text, we created a program to track the right number of keywords in the source text and the translation. With this program’s help, we knew both the right number of active words for each character as well as the specific locations for their use.

Apart from the keywords that are repeated within a location, there are also keywords that are used throughout the game. These words are taken into account for all locations and characters. Once we were done testing the character texts, we needed to ensure that keywords from the game world didn’t overlap with location-specific keywords.

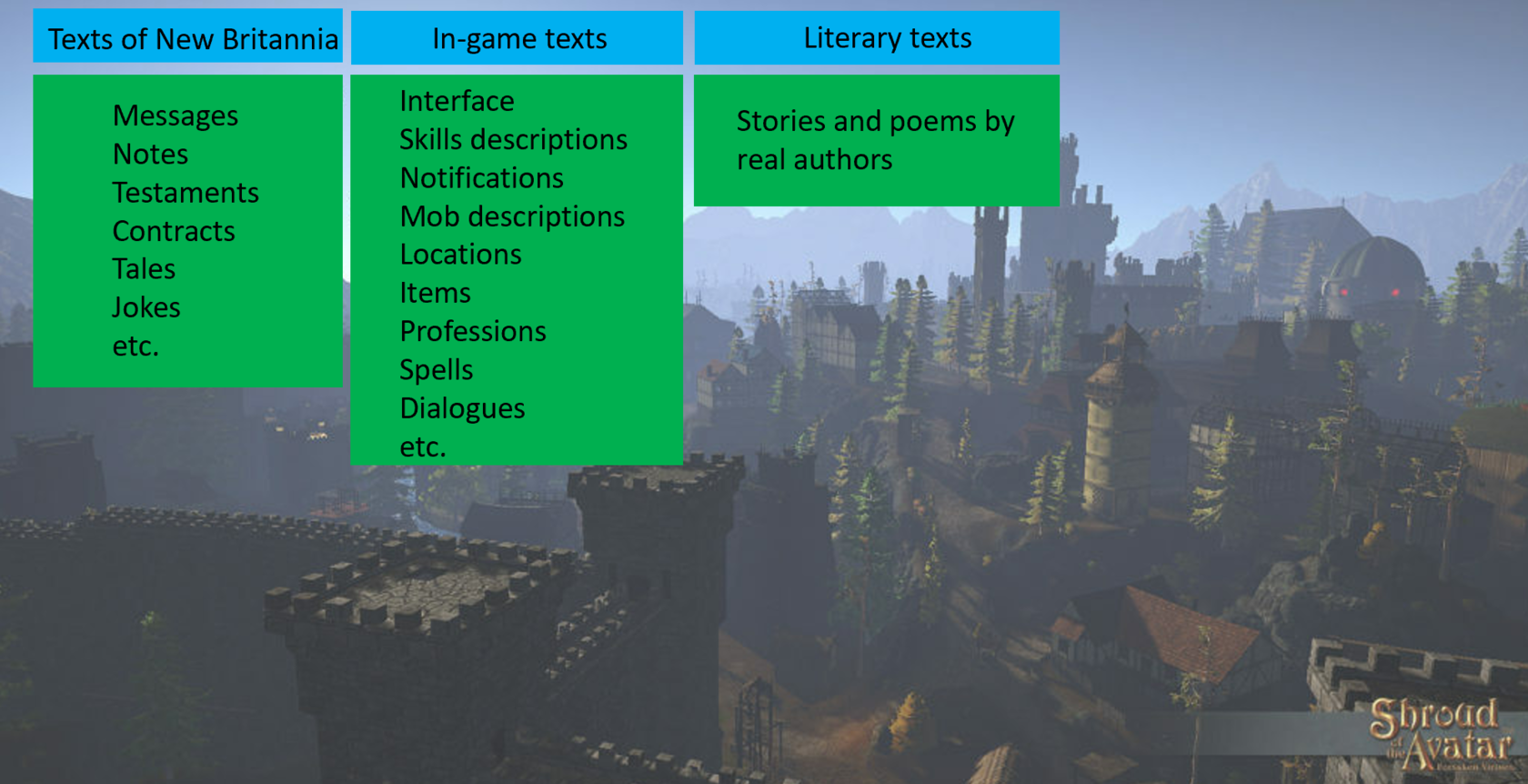

In Shroud of the Avatar, the world is based on both the real and the unreal: the ideas of Richard Garriott’s team stand beside the stories of Middle-earth, and the people of New Britannia read Edgar Allan Poe and quote the continental school of philosophy. We translated a huge amount of literary text, both published works and books written specifically for SotA. Tracy Hickman and Richard Garriott wrote the longest in-game book, with a wordcount of 75,000 words. As no other game features any literary works of that size, it’s quite an exceptional case.

We created new translations for the texts that had already been published in order to avoid copyright issues. These were mostly excerpts from small mysticism and fantasy stories, couplets, and simple poems. Here are some of them:

- Edgar Allan Poe: The Black Cat (Spirits of the Dead, The Village Street)

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft: The Beast in the Cave. The Nameless City. The Alchemist

- Clark Ashton Smith: The Beast of Averoigne

- Gertrude Atherton: Death and the Woman

- The Brothers Grimm: The Wolf and the Seven Young Goats

+

=

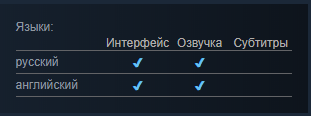

You’re probably wondering where the other localizations are, and we’re going to try and answer. So, where are the other localizations?

The other localizations ended up on Zanata — a space where any player can assume a translator’s role. We could say it was a one-way trip one doesn’t return from, or joke that descending into the underworld and coming back would be way easier, but it’d be more useful to try and figure out what happened.

We’re not going to discuss the global issues of community translations (not now, at least). Instead, we’ll examine the black box of the SotA translation. According to SotaWiki, the Spanish, French, Italian, German, and Portuguese versions were delegated to the community.

On March 8, 2013, Shroud of the Avatar: Forsaken Virtues was announced in Texas. In less than two years, the first translation files for the new game appeared on Zanata. As expected, many people wanted to take part in the SotA translation. Everyone wanted to contribute to the new game, not just virtually, but also in real life. However, player hopes were smashed down by the harsh realities of localization.

Almost all of the respondents had no experience in translation whatsoever, but wanted to participate really badly. We can only assume they imagined themselves spending nice, long evenings pondering over how to convey the hero’s thoughts and the hidden hand of the author behind them. However, the process ended up being much like the our own when we were working on the Russian version. Thing is, there were no translation teams, no clear task distribution, no proper software, nor was there any kind of incentive on Zanata. Most people just weren’t ready for on-screen text, skill descriptions, deadlines, and the monotony that comes with the less-than-romantic translation process.

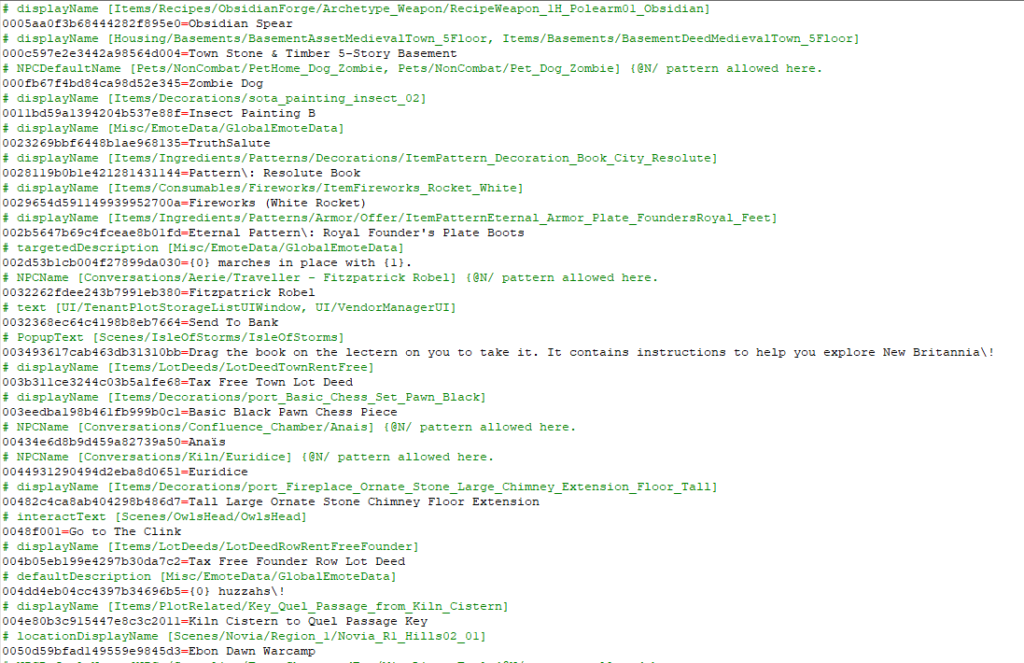

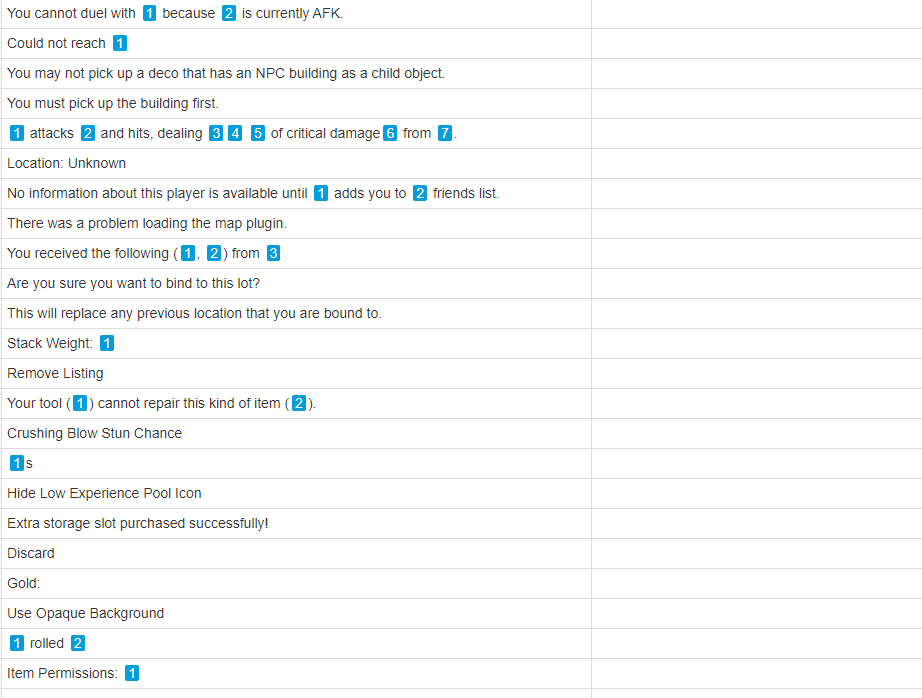

A .po file in its natural habitat, Notepad++, as seen by the community translators.

A .po file in Memsource, lovingly prepared by a project manager.

Everyone wanted to translate dialogues and literary content while staying away from the rest of the text. Cue arguments, grudges over text distribution, and hasty departures from the project. In the meantime, text batches kept arriving… The huge army of Garriott’s fans ended up only detracting from the new game. There’s a world of difference between localizing texts for money and translating them merely out of respect for the game.

In the face of a full-on retreat, only some enthusiasts stayed on the forums to continue with the translation, but that simply wasn’t enough. The German players outranked everyone else, managing to translate nearly half of the text. In the end, the community translation was called off before the Russian localization was finished, and is now infamous for its lack of organization, and the discord it bred.