What is the purpose of localization?

A brief (not really) intro by Levsha

Question: how do you know that a videogame got the localization it deserves? Answer: you never even pause to think about it. An entire team of localizers puts in tremendous effort to make sure users from a completely different culture, speaking a totally different language, will like the game. A localizer’s craft intersects with a translator’s, but there are a few important distinctions, nuances, and unique challenges.

What is the purpose of localization?

Localization is a relatively young industry. It got its start way before videogames came around, naturally. Long before the first gamer completed the first game on their computer (or console), people around the world were clamoring to watch foreign movies, and even before that, they were yearning to read foreign books.

“But that’s not really localization, is it,”—you might be asking right now,—”That’s just translation!” That’s not quite so. Localization and translation intersect, yes, but they are not the same thing. Localization tackles more challenges, it involves more people, and its scope is not limited to text.

Product Localization = Product Translation + Cultural Adaptation

Is it not enough to simply translate the text? No, it is not. You see, any popular cultural product is loaded with cultural code from the place of its origin: habits, traditions, an outlook on certain things, religious canons, etc.

Nota bene:

Verbatim (interlinear) translation is NOT a meaningful translation. The translator’s goal is to convey the meaning of the text and not just the individual words in it.

The Holy Grail of translation is a Good Translation: one that does not lose any of the original meaning or connotations while the meaning itself can be comprehended in full.

Localization is a Good Translation and then some: readers and viewers must be able to comprehend everything they see on the screen. Moreover, everything they see must be legal and land somewhere within their cultural boundaries. Essentially, cultural adaptation of a given work must be successful.

Cultural peculiarities of a given country are always reflected in its language. There are no language pairs where words and colloquial expressions are summarily equivalent to one another. If there were, a verbatim translation would not feel as awkward as it does and the jokes in it would not be so perplexing.

Popular culture is full of humor based on wordplay. Here is an example from the TV show Friends — in one of the episodes, Rachel and Joey have the following exchange while talking about a handbag:

Source:

-Exactly! Unisex!

-Maybe you need sex, I had sex a couple day ago.

-No, Joey. U-N-I-sex.

-Well, I ainʼt gonna say no to that!

-Maybe you need sex, I had sex a couple day ago.

-No, Joey. U-N-I-sex.

-Well, I ainʼt gonna say no to that!

The wordplay here is simple: “unisex” sounds a bit like “you need sex”; then, when Joey hears “U-N-I-sex” he interprets it as “you and I sex.” Since this wordplay is based entirely on phonetics of the English language, it is almost impossible to translate literally into another language.

If you were to translate this exchange verbatim into Russian, the joke would completely evaporate:

-Именно! Унисекс!

-Это тебе нужен секс, я занимался им пару дней назад.

-Да нет же, У-НИ-секс.

-Ну как от такого отказаться!

-Это тебе нужен секс, я занимался им пару дней назад.

-Да нет же, У-НИ-секс.

-Ну как от такого отказаться!

There is a lot one needs to keep track of: colloquial expressions, sayings, cultural and historical references, meaningful names, toponyms, etc. To further illustrate this point, let’s consider the difference between translation and cultural adaptation of the following phrase:

Source:

-Апчхи!

-Будь здоров! Блин, чувак, ты выглядишь так, будто скоро склеишь ласты.

-Будь здоров! Блин, чувак, ты выглядишь так, будто скоро склеишь ласты.

Verbatim translation:

-Ahchoo!

-Be healthy! Wow, dude, you look like you’re about to glue your flippers together

-Be healthy! Wow, dude, you look like you’re about to glue your flippers together

Good translation:

-Ahchoo!

-Bless you! Oh, man, you look like you'll kick the bucket soon.

-Bless you! Oh, man, you look like you'll kick the bucket soon.

We have a couple of idioms to work with here, and both have some meaningful context to keep in mind. In the Russian source, the first expression is very straightforward: you wish good health to a person who shows a symptom of sickness to show that you mean well. In English, the same connotation is conveyed by a phrase rooted in an antiquated belief that a person’s soul briefly leaves the body when they sneeze — so you have to bless the sneezing person quickly before a wandering demon can snatch their soul. The original belief is long gone, but the expression remains.

The second expression is “склеить ласты” (to glue your flippers together) — it’s one of the many fairly abstract euphemisms for dying in Russian language, along with “сыграть в ящик” (to play the wooden box), “дать дуба” (to go oaken). These expressions allude to ending up in a coffin and the onset of rigor mortis, respectively. The English equivalent—to kick the bucket—does not convey any meaning beyond the sum of its words when translated into Russian, whereas in English it is believed to originate from a Medieval execution method: when people were hanged, they first stood on a bucket, then the noose was tightened, and the bucket was kicked out from under them.

In cases like the one we just reviewed, it’s important to convey the original meaning in a way that a person who belongs to another culture and speaks a different language would understand, all in a way that the author of the source text intended. At this point, however, we are still talking about translation (a good, high-quality translation) and not localization.

Localization proper means changing the product in some meaningful way that goes beyond switching a few words or phrases around. Localization deals with changing certain implicit meanings and cultural concepts. Here’s an example: when localizing the game Injustice: Gods Among Us for UAE and Kuwait, the localization team had to change the game’s release title to Injustice: The Mighty Among Us because in Islamic culture the word meaning “multiple deities” is deeply problematic since it goes against the postulates of Islam. The localization team had to make adjustments to the product itself with the cultural peculiarities of their audience in mind — that’s what localization is all about.

Videogame localization

A good translation can make or break a videogame experience. When you don’t catch the meaning of what a movie hero just said, you can watch on just fine. In a videogame a misunderstanding can cost you a quest reward. If a trader asks for 25 Imp Eyes and the enemies in the game that drop them aren’t actually called Imps, you’re going to have a problem. All your eyes are belong to us? Not gonna happen.

You will have a better time with a game when you understand what’s going on without having to decipher foreign expressions and references. It’s nice when you can just pick up a game and play it, isn’t it?

Will any player feel compelled to finish the game if every other phrase resembles a product name on Wish.com or a direct insult?

Running the texts through Google Translate just won’t cut it: instead of coherent text you get a text-resembling word salad.

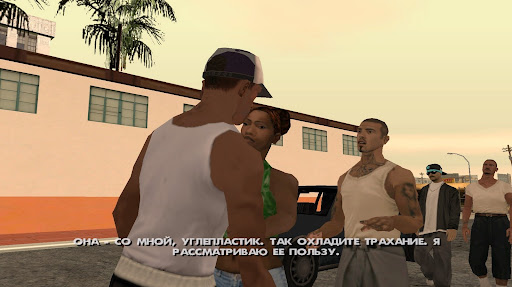

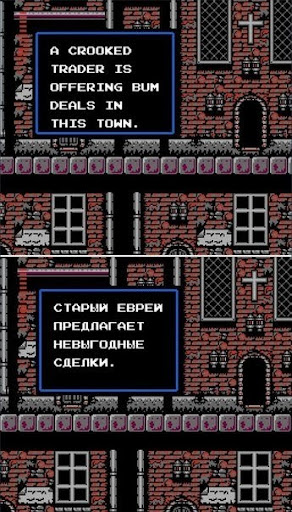

One of the most notorious and commonly known examples of bad translation is the first localization of GTA: San Andreas. In the Russian gaming community, it is considered the “gold standard” of bad localization, and some of its terrible translation choices persist through time as memes.

Chief among them is the way the word WASTED on the character death screen was translated: in Russian, it said “ПОТРАЧЕНО” (“SPENT”). While it is possible to interpret the source as “wastefully spent,” the original meaning is rooted in the colloquial use of the word that puts it closed to “killed” or “murdered.”

Mistakes like these are common among unlicensed and fan-made translations: these projects aim to launch the game into a new market as soon as possible and capitalize on it with little regard for quality. Professional localization has processes in place to detect and fix mistranslations like these. Translators, editors, and localization testers work together to iron everything out.

The meaningful content is not the only thing a localizer has to keep in mind when working with game materials: there is also word agreement, character limits (some text has to fit in a limited space), translation variability, and a lot more. These are just some of the ways localization is different from regular translation.

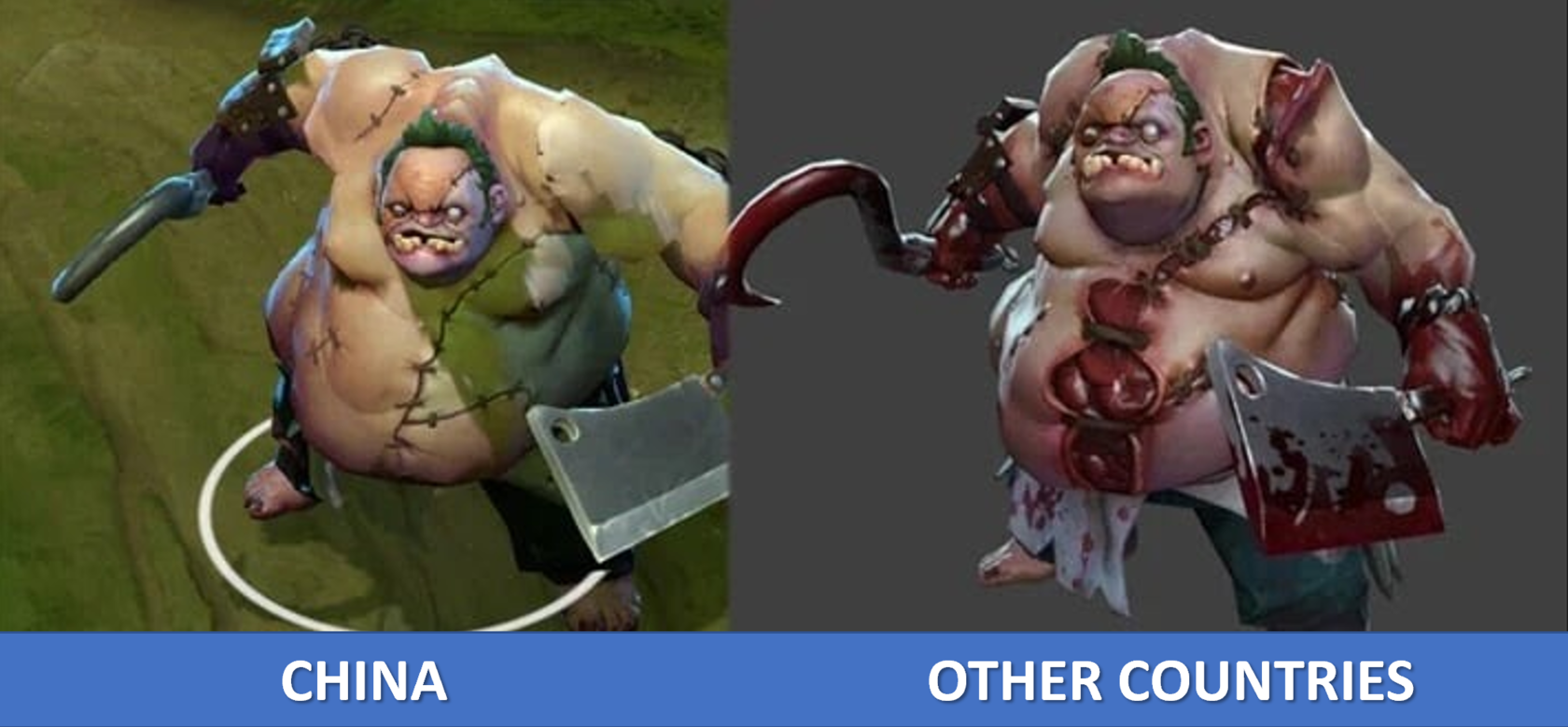

Localization is not limited to text alone, either. Localization experts are often faced with far more complex cultural and legal challenges. Laws in the country where the target audience lives may be different from the ones in the country of origin, which could necessitate certain changes. Some plot elements could be legal in the country where the content was made but illegal in the one where it is distributed. These elements have to be blurred out or straight-up cut from movies, but in games the localizers have to go even further.

This is point is illustrated best by the Nazi imagery depiction laws around the world. For instance, for the German release of Wolfenstein II the localizers had to replace the swastika with a different symbol and even shave off Hitler’s moustache.

Another lesser known example: in China, it is illegal to depict blood and gore. The localization team working on DotA 2 put in some serious work to bring the game to the Chinese market: some character skins had to be completely reworked.

As you can see, localization can save the people releasing the game some serious pain from scandals and lawsuits that they would inevitably suffer if they only went with a straightforward text translation.

Localizers: who are they?

Long gone are the times when releasing the game in another country only required some translation work. Releases are now competing for gamers’ attention and that fosters innovation within the industry. Quality translation? You got it. Dubbing character voice lines? Can do. Texture redraws? Sure. Everyone chips in and it all amounts to good localization when it’s put together.

That’s the Levsha way:

Big Boss x3

Cookies, Cats

Staff members:

-Sound Engineer

-Voice Director

-Loc Managers

-Business Development Manager

-Vendor Manager

-QA Manager

Outsource or staff members:

-Translators

-Editors

-Proofreaders

-Testers

-Designers

-Actors

Big Boss x3

Cookies, Cats

Staff members:

-Sound Engineer

-Voice Director

-Loc Managers

-Business Development Manager

-Vendor Manager

-QA Manager

Outsource or staff members:

-Translators

-Editors

-Proofreaders

-Testers

-Designers

-Actors

Localization manager negotiates the details with the clients and sets the deadlines. The client creates the lockit — a package of files Levsha needs to translate the game. Lockit typically comprises every text component of the game, its glossary, and technical documentation.

When that’s done, translators step in: they translate and adapt the game text into a new language, carefully considering the laws and cultural environment in the country where the target audience resides.

Then the editors get to work: they go over the translation and ensure its cohesion, fixing the things that could be done better and correcting bad segments. If the translation is summarily bad, it can be sent back to the translator for a do-over.

Technical specialists are handling the wibbly-wobbly file formats, deconstructing them and putting them back together as necessary. They also handle the integrations and automation processes linking the files with other tasks. Designers create new graphics to go with the new text if necessary.

If the game has to be dubbed, voice actors will record character voice lines and background narration. Sound engineers work with them to put it all together.

Once all that is done, the game build is given to the LQA testers — their job is to make sure the translation is good and that it looks good in the game. They check all the text boundaries, make sure the fonts fit and the dates are noted in a way that the target audience will expect, etc.

What is it that a localizer does, exactly?

You could say that everyone working in this industry is, to an extent, a localizer. But no matter how you spin it, translators are the backbone of this industry at the core of what localization does. When people say “localizer,” they mostly mean “translator”.

At this stage of the workflow, the localizer’s goal is to make the game text presentable. To do that, it’s not enough to just be proficient in a foreign language: it’s important to understand how that language works in different situations and where it’s meaningfully different from one’s native language.

Things to know and ways to learn them

You have to have a good feel for both the source and target languages. You need that language sense to translate and pick the best means of expression for any given situation. A good feel for the language will help you to pick a synonym that will fit into the context and won’t accidentally offend the native speaker. This is the bare minimum of what you should be capable of.

You have to be naturally curious and ready to figure anything out.. There is an abundance of themes you can encounter in videogames: one day you’re localizing a WWII game, and the next day you are working with a game set in Ancient Egypt. Vocabularies and text styles will differ drastically across different games. You might encounter highly specialized terms, especially in military games. A good localizer is a walking dictionary. Being well-versed in certain fandom cultures will help, too — there are a lot of games out there that are set in well-established universes, and navigating your way through the communities built around these universes will undoubtedly yield a wealth of knowledge about characters’ lives and temperaments, which is invaluable to a localizer.

You have to have some gaming experience. Some gaming basics—what is a quest, how is PvP different from PvE, who is the DD, or DPS—will go a long way in helping you figure out your work. An experienced localizer will know better than translating “Damage” as “Повреждение” in combat context or “Credits” as “Кредиты” in the context of a main menu. You might struggle to find employment in the industry without any game experience, but the good news is that it’s never too late to get some.

You have to be proficient with certain professional software. Major localization studios use CAT (computer-assisted translation) tools in their workflow. You should be able to work with these CAT tools, and the more well-versed you are on the technical side, the better your chances.

You have to know your world history and be aware of contemporary geopolitics. A game where the Chinese army marches into Seoul probably won’t sell in South Korea and a game fielding criticism against the Quran will cause an uproar across the Islamic world. These controversies should be handled by the developers, but the localizers can facilitate the adaptation process and weigh in on how to smooth any particularly sharp edges.

Every year a team from Levsha is offering a Localization and Translation Workshop within the framework of the Summer School. There are five people on our staff right now that we met during one of the workshops. More info about the Summer School is available here.

Higher education is catching up to the progress made within the industry. The Higher School of Economics in Russia offers educational programs that touch on the localization processes: Game Project Management and Basic Game Creation.

Professional conferences like Translation Forum Russia and Hyperbaton are a great place to make some useful connections, share your experiences, and slide into the game industry.

There is also the Gamelocalization school founded by our very own Anton Gashenko. It offers courses for beginner localizers and advanced learners.

Who is hiring and how is the pay?

Thousands of videogames are released around the world every year. Developers want their games to sell in as many markets as possible. There is plenty of localization work to go around.

Localization studios are often hiring translators and editors. Some game developers have their own localization staff. Generally speaking, this industry is mostly looking for freelancers.

Where do I look for jobs?

- Go to the website of the company where you would like to work and look for the Careers section. Get in touch!

- Check out the translator work aggregators: translationrating.ru, proz.com, ru.smartcat.com.

- Look for relevant work on game industry work aggregators: ru.ingamejob.com, talentsingames.com.

- Keep an eye on dedicated Facebook groups, Telegram channels, and other social media.

- It won’t hurt to try the good old hh.ru and dedicated websites like dtf.ru but don’t get your hopes up: relevant opportunities there are few and far between, and well-paid ones are a rare sight.

Our studio is hiring every now and then. If you would like to work with us, fill out a vendor form.

Your pay depends entirely on your employer and how many projects you are ready to take on. The average industry rate is 1.00 RUB per word and you will be expected to handle 2,500 words per day on average. The better you do and the more you get done, the more you get paid. A skilled professional is always an asset to their employer!

What else is there?

When you get down to brass tacks, game localization—and the gaming industry at large—are not that scary nor impenetrable. If you are passionate about it, you can always find a job to match your interests and capabilities, even if all you have is a Foreign Language degree and a surface understanding of other cultures.

If you can talk the devil’s tongue off and never miss a deadline, see if localization management would suit you. If you have impeccable pronunciation and delivery stacked on top of some acting talent, maybe voice acting is your style. If you can draw anything you see, maybe you can create location and character art for games.

Go ahead and kick open the door on your way in. You can do it!